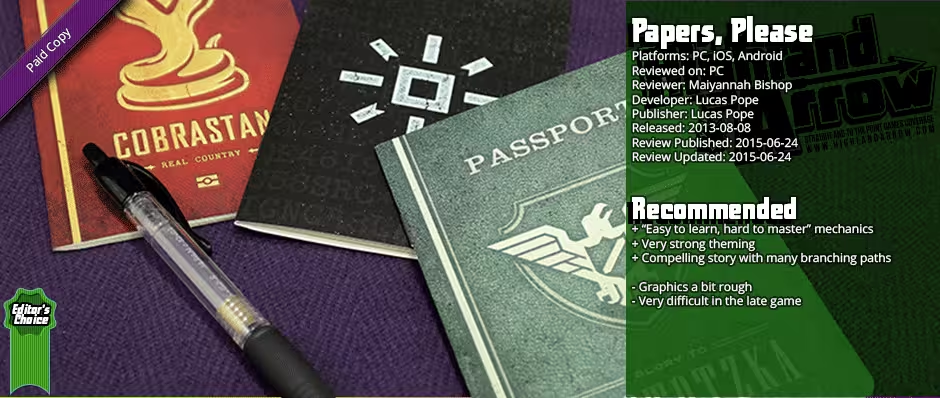

Papers, Please is a sort of puzzle game developed and published by Lucas Pope. Every now and then you come across a game that just does it's own thing so uniquely that it doesn't really fit into a genre neatly, and Papers, Please is one such game. Labelled as a "dystopian document thriller", Papers, Please puts you in the shoes of a border control agent who must inspect passports and other entry documents. Yeah, it's definitely not one that would have survived the elevator pitch to a big-name publisher, but that's just the wonderful nature of indies, and I think you'd be doing yourself a disservice not to give it a try, because what started as a simple little puzzler quickly became one of the more uniquely engrossing games I've ever played. Boiled down to its basest elements, Papers, Please is the best exercise I know of, in giving a compelling game experience that isn't fun, per se. A genuine page-turner, to borrow the literary term.

Papers, Please is a simple game

at face value, mechanically

The thing that Papers, Please does best when it comes to game design is the "easy to learn, hard to master" thing. Essentially, it is a single mechanic: you examine documents and then either approve entry or highlight discrepancies and deny (or approve based on correction). The details are in how it builds on that. You have progressive in game days (about 20min sessions), and each day or two introduces something new to check for. As an example, on the first day, you simply must approve all the citizens of your country, and turn away others. On the second, foreigners are admitted, so you must examine their passports to establish they are legitimate. On the third, they introduce entry tickets with a given date on them, so you must verify the date. And so on and so forth. And that's how Papers, Please simply, but masterfully,

It is genuinely hard to play a good person

The crux of any moral choice system has to be consequences for each of the actions, and this is what Papers, Please does so well. In Papers Please it is genuinely difficult to be a good person, and that is what makes the act of doing so valuable. Something which comes easily, goes just as easily, and in making it difficult to find the game paths one might say are the "moral" ones they make those paths all the more rewarding. This is what so many binary moral choice systems do wrong, in my opinion: to my mind, the "evil" path is usually the more immediately profitable one, but also dubious, and perhaps with long-term consequences. it's the path of short-sightedness to me, in other words, whereas the generally moral path may involve sacrifice, or perhaps just not pay out immediately, but it is for someone playing the long-game, whom knows that a history of right actions will pay off in the end.

For it's part, there's an ending that very much feels that way both as someone trying to be a good civil servant and simply discharge the duties of their station as a border agent, and there's the one that helps the rebellion against the (heavily) implicitly communist regime. I won't get any further into it as I've already broached into the kind of spoiler territory that leads to mobs with pitchforks and me being weighed on a scales against a duck for some peculiar reason, but suffice it to say there are quite a few endings to the game, and while some of them are basically of the "non-standard game over" variety, many more feel like a true ending for better or worse. That's another trap of the binary moral choice system as well - usually the "evil" or less morally-desirable path's ending just feels like such a "non-standard game over," and Papers, Please deftly avoids that pitfall.

Visually the design has some flair, but the graphics are lacking

Lets not beat around the bush here, the graphics style, while it does have a certain flair and obvious care given to it, is very dated looking at best. While some games like Shovel Knight manage to transcend, a lot of the time I find Papers, Please to be merely serviceable. Now, serviceable is not bad, lets just state that firmly now before I move on, but I'm not sure how well-served the game is by the pixel look. Don't get me wrong, I know why the game is designed in such a way: if the game had cutting edge graphics and the like, it would be very obvious when the photographs on the passports didn't match up, unless a significant amount of care was given to designing around that, and that is why you have comparatively simple graphics here, make no mistake. It serves that purpose well, to be fair to Papers, Please.

Ultimately, the game seems to make a fair use of mostly-vector graphics in it's appearance, however, so I'm left wondering why it simply didn't go all in and do some great vector graphics. I cast my mind back to the Delphine Software Another World (aka Out of this World), whose vector, polygon-style graphics were very simple, but have retained a sort of timeless appeal to them for the nature of them. It could have elevated the graphics from merely okay to really kind of excellent in this case, but don't get me wrong, they're hardly bad.

The theming is what carries the game in art design

Papers, Please is an intentionally minimalistic and oppressive-seeming game. This is a game that thrives in the sort of dystopian aspect of that fictional communist country and its neighbours it has woven. And that really is the second major strength of the game, because it does that really well - from that minimalistic interface, to the easily-cluttered desk to examine documents, to the simple handful of notes that make up it's main theme, and beyond, Papers, Please does a very good job of conveying that claustrophobic and uncomfortable atmosphere, and the impassioned pleas of the occasional refugee on the run or the dander of the comedy character whom comes with bad papers several time give a very human element to that struggle that makes it all the more poignant. This is what makes that story and it's choices pay off - it invests you in them, because they feel like real, human choices.

Late-game in Papers, Please gets fairly difficult fairly fast

The only real stumbling block for people in regards to Papers, Please, other than the highly-subjective quibble of the art style I mentioned above, becomes it's complexity and thereby difficulty towards the end of the game. It's a hard game towards the end, without the Easy Mode crutch it gives you, and getting the "true" ending may be all the more rewarding for it, but I've bent many an ear to people who stopped short of the ending because it was simply too difficult for them, so it seems well worth mentioning. The problem is there becomes so many different things to check and cross-check that for someone with a bad memory (guilty as charged myself), there come s very Dark Souls -esque wall at a point. While you can push past it, it'll certainly be a detriment to some. I'm a little on the fence about this one though: while it is certainly there and I dealt with it myself, I found I'd more than got my money's worth out of the game before that point, so I find it difficult to fault the game too much for it.